The feasibility of the door-to-door Covid-19 vaccination campaign is still being debated, as many opposition party officials have requested the center to launch a door-to-door Covid-19 vaccination drive. Earlier last week, the president of the Karnataka Congress, DK Shivakumar, slammed the government for encouraging people to enroll in the Covid-19 vaccine online and demanded that the government launch a door-to-door vaccine drive to persuade people to get vaccinated against the deadly disease.

However, even if such an order is issued, there are concerns in the country over the door-to-door COVID-19 vaccination drive. Only the oral polio vaccine has been administered in India by door-to-door campaigns (which are often limited to ‘Mop-up rounds’) Due to the concerns over possible side effects from vaccination, there has been no such drive towards injectable vaccinations.

That being said, there is a counter-argument: India, which began its polio vaccination program in 1995 and registered its last case in 2011, already has a well-developed network of healthcare personnel. About 2 million staff would administer oral polio drops to approximately 172 million children on a typical vaccination day. In light of the current situation, when our healthcare infrastructure is collapsing, how effective will a door-to-door Covid-19 vaccination campaign be?

So, let’s take a look at the uncertainties in door to door Covid-19 vaccination campaign

Indeed, door to door vaccination campaign may be used to eliminate virus reservoirs. However, there are several issues: Dosages (single vs. multiple) and administration routes can have a significant impact on costs and logistics. Additional training of healthcare professionals will be needed for injectable, intranasal, microneedle array pads, next-generation jet injectors, oral tablets, or sublingual oral gels. Besides that, rigorous epidemiological tests for antibiotic resistance would be needed and experts say that there is a high chance that this will jeopardize the lives of healthcare workers. Apart from that, stocking of PPE, back-ups for logistical burnouts, transportation efficiency, and the immediate need for electronic monitoring are among the additional problems.

Going door to door requires placing the temperature-sensitive vaccines in and out of the carrier before and after each jab. As a result, the temperatures required to store the vaccines would be almost impossible to sustain during the journey. Temperature fluctuations would eventually make the vaccines ineffective.

High wastage drives up vaccine demand and increases procurement and supply-chain prices. For instance, the Covid-19 vaccine vial should be given within four hours after it is opened. Otherwise, they would be tossed away and destroyed. A Covidshield vial contains ten doses, while a Covaxin vial contains twenty. For one human, each dosage is 0.5 ml. When considering the time taken to travel from one house to another, a door-to-door drive would result in significant vaccine wastage. Any squandered dose is a financial drain on the government’s coffers.

Experts believe that the door-to-door covid-19 vaccination drive would be difficult due to the country’s crumbling health infrastructure. During a door-to-door campaign, it may be difficult to decipher procedures for physical distancing. Also while looking at the fact that the majority of people who have had an initial dose of the vaccine have not received a second dose. Slots are limited, and even if you find the slot, hospitals are running short of supplies.

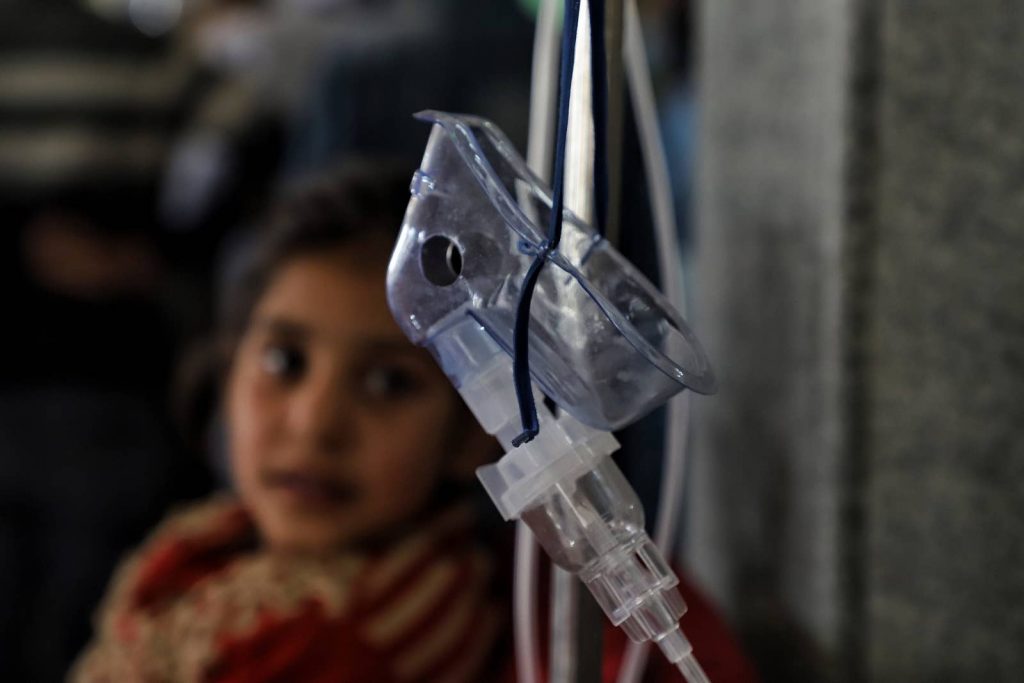

But here’s the thing: the door-to-door campaign will only exacerbate the country’s problems. Considering the current situation, the number of cases and deaths in the country is rapidly increasing, thanks to the massive election rallies and faulty governmental policies. Testing is increasing, but so too are the number of positive results. The country has a chronic shortage of space on its intensive care wards forcing many patients’ families to travel miles in order to secure a bed for their loved ones. Hospitals in Delhi, which has a population of around 20 crore residents, are overcrowded and are turning away new patients. Doctors have described that people are dying on the streets outside hospitals. Hospitals all over India are running out of oxygen, and some have had to put up signage warning of a shortage. How effective can a door-to-door vaccination campaign be under these circumstances?

Let’s take a look at the major flaws in our current vaccination campaign.

In the United States, the vaccine campaign was divided into three phases: first, for people aged 60 and above, then for people aged 45 and above, and finally for people aged 18 and above. Vaccination clinics were packed with people eager to get their shots. There were no legal snags, and even illegal immigrants in the United States received vaccinations. The outcome is clear: about 40% of the US population, have been completely vaccinated. In addition, 65 percent of the older population has been completely vaccinated. The number of new incidents and deaths has both decreased dramatically.

We must note that India is not the United States. We have a population of 100 crores greater than the United States. And even if we increase vaccine rates, it would take a long time to achieve our goal. Furthermore, mandatory vaccines for all Indians above the age of 18 years might not be possible anytime soon. There is insufficient vaccination

When India introduced its coronavirus vaccination drive in mid-January, the chances of success seemed high: India had the capacity to manufacture more vaccines than any other country and had decades of experience inoculating pregnant women and children in rural areas.

But the initial promise has faded just over three months later, and the government’s policies are in disarray. India has vaccinated fewer than 2% of its 1.3 billion citizens, inoculation centers across the world are running out of doses, and shipments have been completely halted. As just a second wave overwhelms hospitals and crematoriums, our nation is setting regular records for new diseases rather than building defenses.

To consider other countries including UK and the US are treating patients with Pfizer vaccine which has a higher efficacy rate but the Pfizer vaccine has been delayed in the country. As there are price and export constraints. According to one of the reports, Pfizer and Moderna, whose shots are much more expensive than those used in India’s immunization program and hence the government approved two much less expensive vaccines in January: one from Oxford University/AstraZeneca and another produced in India by Bharat Biotech in collaboration with the Indian Council of Medical Research. The Pfizer vaccine’s stringent storage and transportation requirements make it impossible to introduce mass vaccination plans in a country like India. The vaccine needs an ultra-cold chain with a temperature below minus 70 degrees Fahrenheit, and it is not possible in India. For the time being, a third deterrent is a cost. It is more expensive than the others under consideration, costing nearly USD 20 per dosage.

Besides that, health care facilities in India are heavily reliant on the private sector. As a result, private hospitals will play an important part in ensuring that patients are vaccinated as soon as possible. But the vaccine manufacturers have requested them to wait 6–8 weeks, and import is not an option as manufacturers have stated that they will only work with federal agencies. Private hospitals aim to procure directly from manufacturers, but the Serum Institute of India and Bharat Biotech have said they won’t be able to do so right away because they agreed to sell 50% of their imported vaccines to the Centre and 50% to the states.

On May Day, many activists claimed that there is a severe vaccine crisis and that in the middle of this, the government’s vaccine policy prioritizes corporate interests above people’s precious lives. According to the Central Trade Unions, it is essential to closely monitor the whole vaccine procedure now, under direct government supervision, to guarantee that the entire populace is vaccinated within a set time frame. To effectively deal with the shortage, vaccine manufacturing must be rapidly scaled up.

The reason India was successful in tackling poliovirus was due to Extensive international partnerships, strong political powers, non-profit funding, equitable vaccine allocations, vaccine provision through governmental schemes (i.e. free), robust logistics, rigorous administrative planning, deployment of the trained healthcare workforce, high population coverage, and strong logistics.

But, since the beginning, the Covid-19 vaccination drive has been plagued by various flaws that have been pointed out by critics but ignored by the current ruling party. The policy has been altered, but only on an ad-hoc basis. There was no comprehensive plan designed and the government continued to do as they pleased, whatever suited them, or whatever served their true intent, whether known and unknown. It resulted in a complete inability to contain the propagation of COVID-19’s second wave, which began in the first week of February.

As India’s healthcare system stretches to breaking point, many patients are succumbing to infections in their homes or on the roads, without any medical assistance. Crematorium grounds and mortuaries in India have run out of space to bury the deceased, and the workers are struggling to perform the last rites due to a shortage of equipment and manpower. India’s vaccination drive is faltering and now the major concern is how will India expand vaccine supply to reach another 600 million populations. Vaccination rates are down across the country due to shortages, despite the fact that more than 10 million people registered for doses and most of them haven’t even gotten a slot.

References:

Image Source:

Associated Press

Pixabay