Edlyn Cardoza | 20 February, 2021 | Mumbai

On February 21, 1952, the protests had erupted, in then East Pakistan against the imposition of Urdu dispatched the Bengali language movement in Bangladesh, and is the core of the International Mother Language Day. In 1999, the UNESCO recognition came in, declaring it as a day to observe and celebrate native languages all across the globe. The wish was to sustain and develop the native language or the first language, and protect the precious heritage of world languages. In reality, is it actually happening though?

Like most ethnic cultures, indigenous languages, increasingly have a localised and restricted existence – overwhelmed by global economics, global markets, and global corporates. The mother tongue is gradually losing life force by these staggering influences and is consigned to a marginal space in the global village. A UNESCO report states that almost 1,500 ethnic languages are globally getting wiped out each day. Their place is being usurped by foreign languages, which encourage and ensure successful trade and commerce and boost the economy.

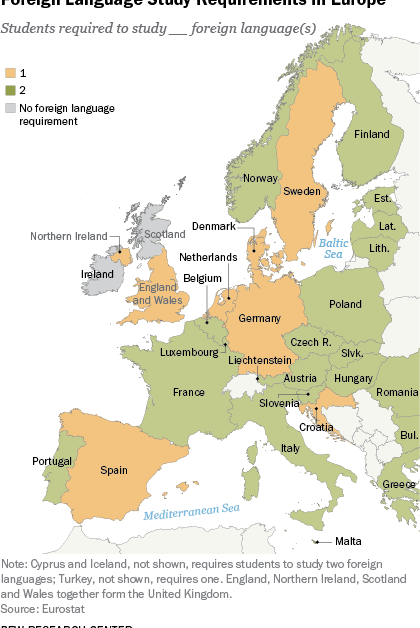

An in-depth knowledge of one’s mother tongue makes assimilating foreign cultures and languages smoother. Nordic nations, after prolonged evaluations and trials, have advocated learning two languages from the primary school level: The language of the land and the mother tongue. In remote areas of countries like Norway and Sweden, where individuals of various ethnicities dwell (mostly migrants on political grounds), as a rule, primary schools teach indigenous languages. It is said that, Bengali is being educated in numerous suburban schools of Sweden, Finland, and Norway. The students are for the most part primary school children and their parents are political migrants; teachers to a great extent hail from Bangladesh while a few are from West Bengal.

Several German states, of late have established this framework, primarily responding to appeals from the Turkish people. It has included Arab refugees since 2015. Bangla, Hindi, Urdu and Tamil are yet to discover a spot mostly because students are fewer and proficient teachers are not quite as easily available. Another reason is also that the number of refugees from the subcontinent is dwindling; extreme laws confine their influx. Nonetheless, Bengalis have been living in the UK for ages. The British Parliament has a significant number of MPs of Bangladeshi origin, who are now British citizens. There are at least a dozen Bangla weeklies published in proper London. Four TV channels (one of them in the Sylheti language) and six Bangla radio stations (FM channels) run out of England. Italy comes a close second as for facilitating the Bengali population. There as well, Bangla newspapers, TV and radio are quite famous. Portugal, Greece and Benelux (Belgium-The Netherlands-Luxembourg) are home to 20,000 people from Bangladesh and West Bengal. North America, of course, is way ahead in this regard. More than a dozen Bangla weeklies are published from New York alone; radio and TV are similarly well known, as are Bangla book fairs and related programmes. The picture is no different in Canada.

Bengalis, thus, seem to have a global presence. Be that as it may, can the same be said of their language, Bangla? Is it promoted and encouraged to develop beyond its boundaries? Not at all. Considering the way that the Bangla language speaking population from the two Bengals possess the seventh spot in the world, the Bangla language hardly holds any significant status. Though the Asian department in the Heidelberg University, Germany, teaches Bengali, the number of students learning it are close to a measly 10. The Berlin Free University no longer holds Bengali classes. And the reason for it? Lack of students. Learning Bengali does not ensure jobs abroad; nor are the youth keen on appreciating Bengali literature. Bengali readers in Germany have barely even acknowledged the works of any Bangla-language poet or author — their interest has halted with Rabindranath Tagore.

In West Bengal, the language of Bangla appears to be vastly considered the language of Bangladesh; Hindi is acknowledged as the language of West Bengal and India. Prior to reprimanding such a claim, one needs to note that nearly 53 per cent of people in Kolkata speak Hindi, said The Indian Express. Billboards in English or Hindi are regularly visible in different localities of Kolkata. In West Bengal, and Bangladesh, parents send their wards to English-medium schools. But are they equally eager to introduce children to Bangla language and literature?

21 February, marks a day of grief and sacrifice, Sacrifice for one’s mother tongue. Yet, the day has assumed celebratory proportions since the freedom of Bangladesh and the ideal at its heart lies forgotten. We can’t blame anybody for this though. The Indian Express wrote, Poetry sessions, literary gatherings; month-long book fairs; the longest-lasting book fairs in the worlds; youngsters crowding bookstalls, imbibing the “culture” of book fairs but not exactly buying books — these are embellishments we chose to be content with.

21 February, is not simply denoted for the movement for the mother tongue;

it led the sapling of freedom to sprout and bloom in Bangladesh. It imparted an exuberance in us. We have been so euphoric about the day that we forget, whether we make merry or we mourn? February 21, 1952 – The Bangla language was born. But I believe we live in our own language and our language lives in us.

References:

Image Sources:

- Newsroom Post

- My Golden Bengal

- Pew Research Center

- Wikipedia

- The Indian Express