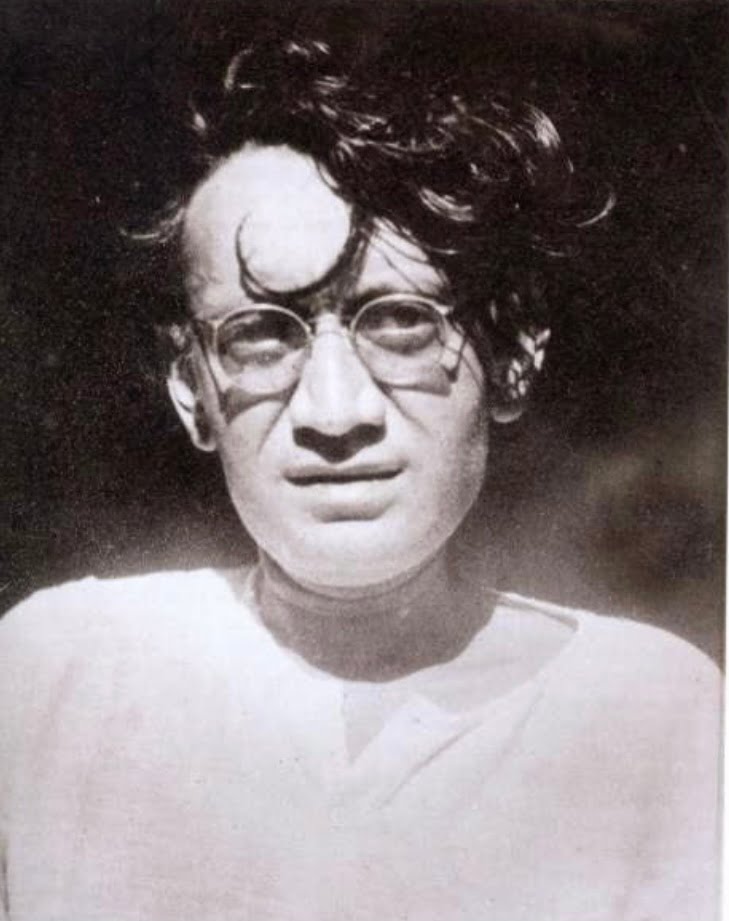

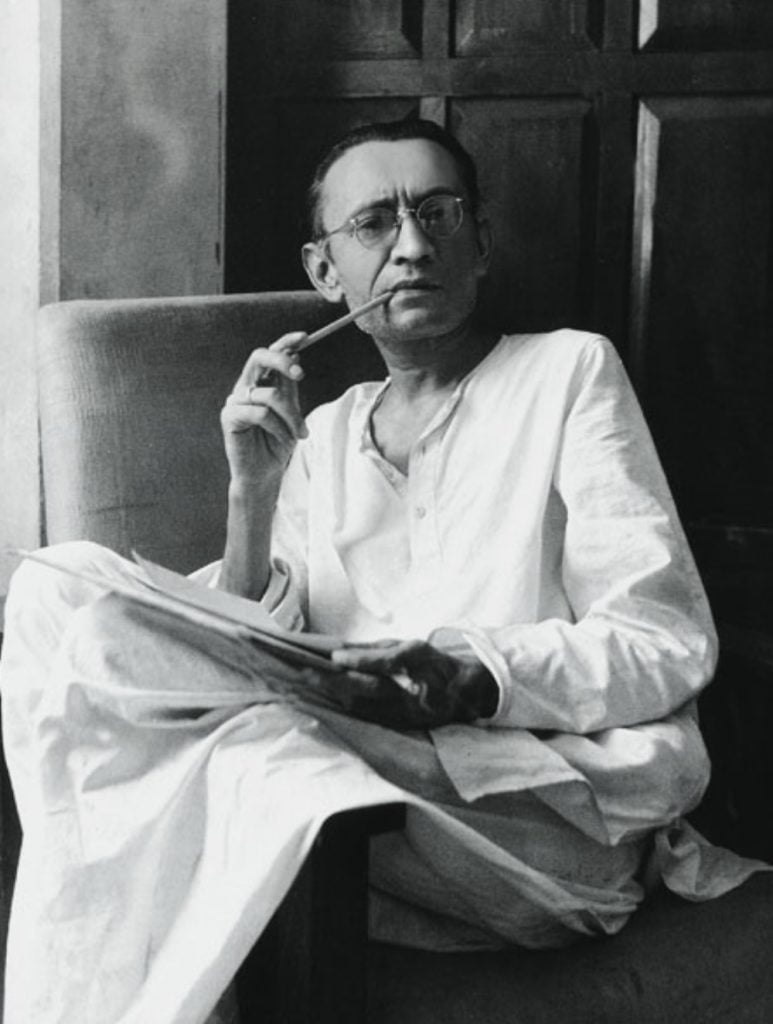

Saadat Hasan Manto was a strikingly prophetic and visionary writer known for his stories about India’s partition. Manto manages to astound writers, theatergoers, actors, and readers even today, having been born a century and a half ago on May 11, 1912. In recent years, a great deal has been written about him. In both India and Pakistan, biopics have been made of him. If you go to a theater in a big city or even a small town, you’re likely to see a variety of plays based on his work being performed.

He started his career as an Urdu translator of Russian and French works, then went on to write short stories, essays, radio plays, and even screenplays after briefly studying at Aligarh Muslim University.

Manto embodied the revolution. He was born with a blazing spirit and squandered no chance to reveal the corrupt underside of his times’ decaying socio-political system. With stories like Thanda Gosht and Kali Salwar, Manto unarguably holds the fort of feminism

He witnessed partition real close, and stories such as ‘Toba Tek Singh,’ ‘The Return,’ ‘A Tale of 1947,’ and ‘Jinnah Sahib,’ invoke the quandaries of people who were caught up in a great internecine massacre.

I wish I had learned about Manto while growing up. But like most millennials, I only discovered Manto after watching Nawazuddin Siddiqui starrer film of the same name. Since then his short stories have inspired me. While reading through his entire collection of “Why I Write,” it restored my confidence in literature as I learned that literature does not have to adhere to a set of rules or be subtle.

I’d use the term enigma to describe Saadat Hasan Manto in a single word. He considered partition to be both brutal and destructive, as well as befuddlingly incomprehensible. In his short story Toba Tek Singh, for instance, one of his characters is a long-term inmate who is perplexed after he discovers that the world has been divided into two parts and that he has no idea where his hometown is. The tale reveals the absurdity of partition through satire.

To characterize massacres, Manto does not use words like “Hindu,” “Muslim,” or “Partition.” He wasn’t obligated to. His characters are real people with real feelings, and their actions are understandable even without labels.

He writes, “Who owns everything that is written in undivided India? Will it also be divided? Is our country a religious country? So we will be loyal in any case, but will we be allowed to criticize the government? After independence, the situation here will be different from the situation of the British government? These lines haunt me even today.

Manto highlights the evils humans would inflict on one another in his short story ‘The Return,’ a chilling tale about a father and his lost daughter.

‘Bombay Stories,’ by Saadat Hasan Manto, is heartbreaking representations of the working class squeezed into slums. Khol Do tells a story of a father who searches desperately for his missing teenage daughter while crossing the border, only to have his happiness interrupted.

Regardless of how awkward the issue was, Manto dealt with the truth and refused to dilute the facts in his stories. He witnessed women’s sexual abuse and refused to ignore the awful patriarchy at work.

Not only that, he was a feminist, he felt that a prostitute’s life had much more sincerity than the lives of so-called honest people who lived under many veils of hypocrisy. In response to his detractors, he famously said, “If you find my stories ugly, the society you live in is filthy.” In my stories, I simply expose the truth.” When one reads Manto, who served as a reflection to the period, one is left wondering why the ghosts of partition still haunt the land and why the scars have not healed.

As Manto’s story brings me to the brink of despair, but Manto as a writer himself gives me a reason to hope. Especially when I’m trying to make sense of the current wave of death and violence, I often return to his piece titled “News of a Killing,” which was originally published as ‘qatal-o-khoon ki surkhiyan.’ Horrified by the endless series of deaths and violence in Pakistan. Rather than advocating for state-sanctioned violence as a means of civil retribution, Manto advocates for humans to change through education. So the least we can do on his birthday is sit and read and re-read his works.

Finally, I’d like to conclude with these astoundingly beautiful lines from one of his short stories: “Agar aap meri kahaaniyon ko Bardasht nahi kar sakte, Toh iska matlab yeh hai ki yeh zamana hi naqabil-e bardasht hai.”

Image Sources:

Getty Images

Design Credit:

Mir Suhail