Edlyn Cardoza | 11 February, 2021 | Mumbai

The recent Chamoli flash flood is an admonition and call to treat our mountain ecosystems with care and sensitivity, plug gaps in the examination.

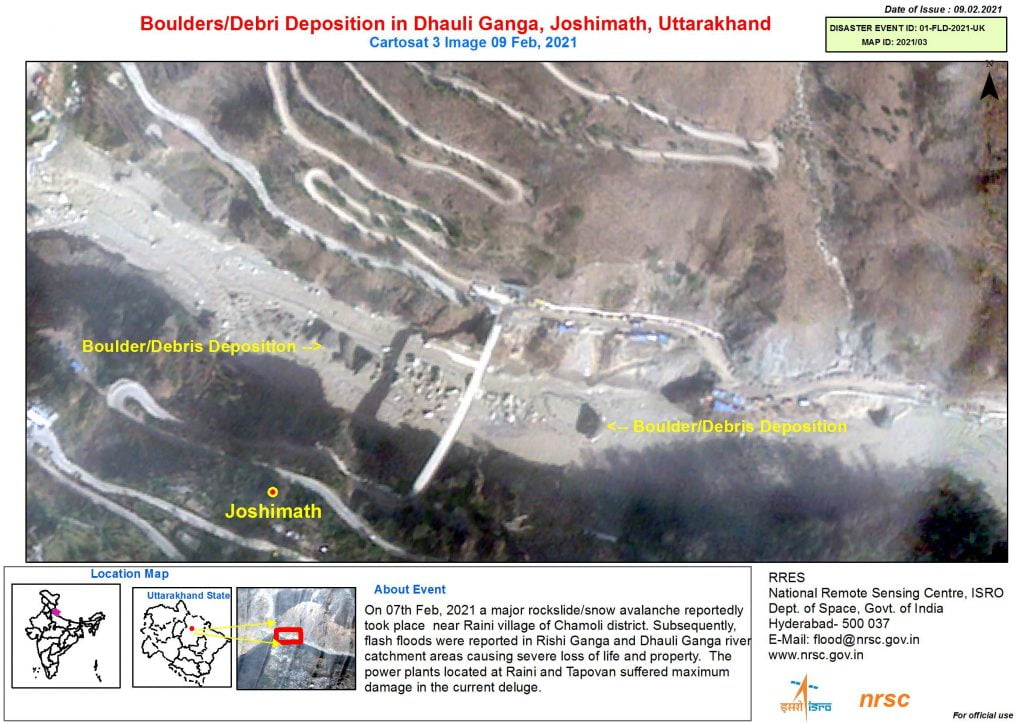

Almost four days after flash floods in the state of Uttrakhand’s Chamoli region swept away the Rishiganga Hydel Power Project, and caused significant damage on the Tapovan Power Project, several workers continue to remain trapped in the slush and debris. The muck deposited by the surge of water, the difficult terrain and the marshy floor have tottered search groups, and 13 villages on the boundary with China stay cut off from the rest of the country. Technological aid, like, robots, drones, and laser imaging have been squeezed into the service to overcome these difficulties, and glaciologists, geologists, and teams from the armed forces have been roped in for the rescue operations. The prompt task before the government is urgent. Yet, the misfortune likewise also outlines another imperative – of re-examining the ways by which mountains and high-altitude locales have been situated in the country’s development discourse. It’s a call to the nation’s science and environment academies to explore and investigate the heap subtleties of Himalayan glaciology and to policymakers to be side by side with such research while taking decisions that impact fragile ecosystems.

Avalanches, landslides, and flash floods aren’t uncommon in Uttrakhand. A developing body of literature, including ISRO data, showcases that practically all the 1,000-odd glaciers in the state are on the retreat. The downstream excursion of the melting masses of ice turns out to be much more hazardous due to the rocks they amass on the way. The first hypothesis for Sunday’s flash floods highlighted to the bursting of one such pocket of water, snow, and rocks. Another early explanation has connected the incident to a landslide brought about by a fracture in a hanging mass of ice, reported The Indian Express. Though the jury is still out on these hypotheses, the link between the glaciers, and the Sunday flash floods appears to be likely. Furthermore, that shout drive home the urgency of combining the divergent data on glaciers and mountain systems in the nation and developing a mechanism to arrange endeavours in this field. D P Dhobal – a glaciologist told The Indian Express in an interview, that, “we need a nodal agency to coordinate all the research…in this region”.

The Himalayas are a young and hence unstable mountain framework. Indeed, even a minor change in the direction of its rocks can trigger landslides. The mountains regulate temperatures in the Subcontinent and, simultaneously, the snow-shrouded ranges are affected by changes in the climate system because of global warming. As of now, Detailed Project Reports (DPRs) of an assortment of infrastructure projects in the region – from hydropower to road construction, do not factor in the idiosyncrasies of this mountain-climate dynamic: They do not represent for the frequency of landslides, snow avalanches, and lake bursts. This gap should be plugged quickly, and detailed examinations ought to be led to comprehend which of the 12,000-odd glacial lakes in Uttrakhand are inclined to flooding. Such research should feed into environmental impact evaluation reports and guide decisions on formative projects in the region. Sunday’s tragedy is a straight up warning that the Himalayan mountains demand greater affectability in policy and research.

References:

Image Sources:

- India Today

- The Statesman

- News18