by Divyakshee K.

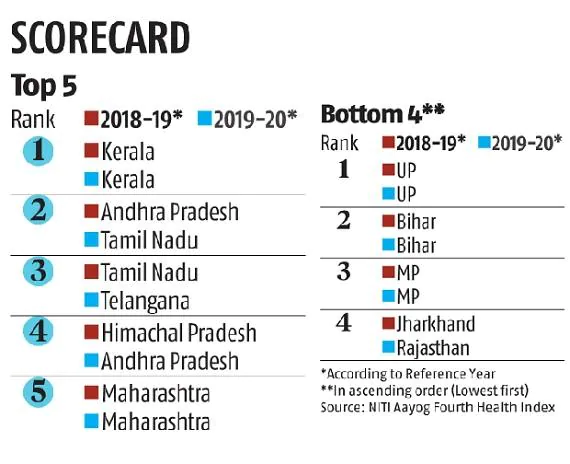

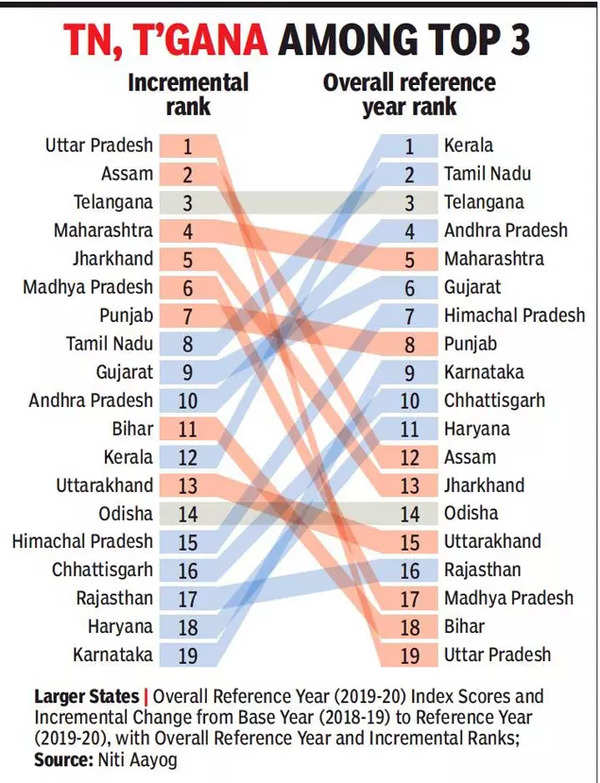

The ‘Annual Health Index,’ announced on December 27, is part of a report commissioned by the NITI Aayog, World Bank and Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. It had a predictable headline: Kerala ranked first. Kerala, Tamil Nadu, and Telangana are the top three, making Kerala the best in overall health performance for the fourth year in a row.

Maharashtra came in fourth place, only one decimal point behind.

Uttar Pradesh was once again the worst-performing state out of the 19 that were examined. Bihar and Madhya Pradesh fared only slightly better, placing as the second and third worst states, respectively.

The index is a weighted composite score that includes 24 variables that encompass essential components of health performance across three domains: health outcomes, governance and information, and key inputs and processes.

The incremental growth rankings from the base year (2018-19) to the reference year (2019-20) show a completely different picture. Uttar Pradesh came out on top, while Kerala and Tamil Nadu were ranked 12th and 8th, respectively.

Telangana was the only big state to do well in both categories, placing third in both.

According to the rankings, which cover the period just before the pandemic struck the country, despite being at the bottom of the heap in overall performance, UP is the best state in terms of incremental performance between 2018-19 and 2019-20. Both the report and NITI Aayog CEO Amitabh Kant made a point to highlight Uttar Pradesh’s ranking as the fastest improving large-state.

However, according to health professionals, there is far more to this claim than meets the eye.

The NITI Aayog computed the health indicators for the year 2019-2020 against the base year 2018-2019. The index is a 100-point scale that assigns a score to each state.

Kerala scored 81.6 in 2018-2019, compared to 82.2 in the previous year – a 0.6-point improvement. On the other hand, Uttar Pradesh’s scores increased by 5.52 points from the base year to the reference year, jumping from 25.06 to 30.57.

T. Sundararaman, a public health expert and global head of the People’s Health Movement, commented on this report saying that “Isn’t it common-sensical that if the baseline is low, the scope of incremental change is the highest?”

The President of the Public Health Foundation of India, K. Srinath Reddy, also made a similar statement. “For a state like Kerala, which has already achieved a lot in maternal and child health indicators, there is not as much scope to improve as it is in improving on the front of non-communicable diseases,” Reddy said. “For states like Uttar Pradesh, the challenge still is to improve maternal and child health indicators.”

Experts also expressed skepticism about the report’s three classifications of states. Arunachal Pradesh, Goa, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, Sikkim, and Tripura were all labelled as “smaller.” Seven Union territories were given the same treatment as the rest of the country. The rest were labelled as ‘bigger.’ (West Bengal declined to participate and the report said that there wasn’t enough data from Ladakh.)

The problem is that the demographic and epidemiological realities of the ‘larger’ states are not uniform. For example, both states at the top and the bottom of the ranking – Kerala and Uttar Pradesh – are ‘larger’. “Since their realities are so different, how can they be put in one basket … and be compared,” Sundararaman asked.

Sundararaman and Reddy agreed that lumping states with such varied health demands together and comparing their performance from the same vantage point would not produce a fair picture.

When all three categories’ states are combined and compared, Mizoram comes out on top with a ‘positive incremental performance’ of 18.45 points, compared to 5.52 points for Uttar Pradesh.

The report is also incomplete, according to health professionals, because its health-outcome indicators do not include noncommunicable diseases and mental illness.

The majority of indicators in the ‘health outcomes’ area addressed states’ performance on maternal and child health, as well as tuberculosis and AIDS to a lesser extent. However, the domain did not account for states’ success in combating noncommunicable illnesses (NCDs).

According to the National Health Portal, 5.8 million people in India die each year from heart and lung disease, stroke, cancer, and diabetes, which are all NCDs. As a result, this is a significant omission.

Another important factor that was overlooked was mental health.

“Due to the absence of these indicators, the report is incomplete [vis-à-vis] gauging India’s health transition,” Reddy said.