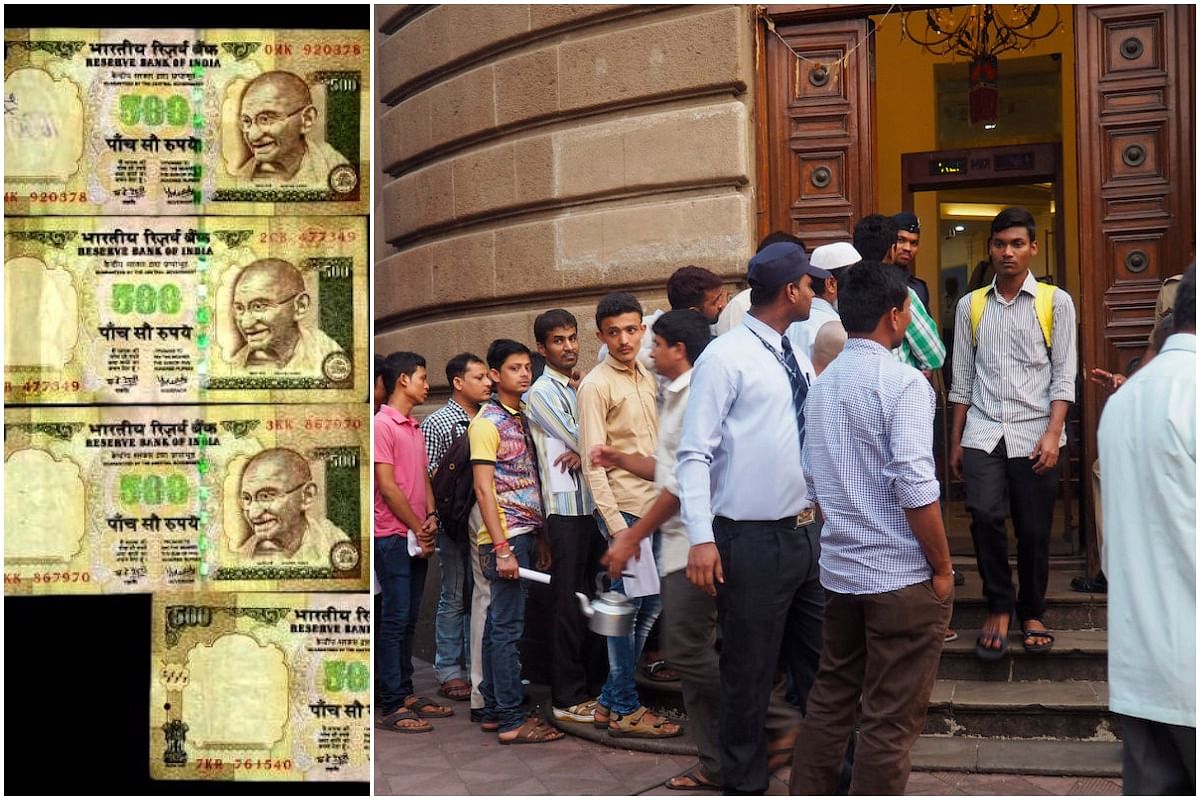

On November 8, six years ago, Prime Minister Narendra Modi had announced the demonetization of old Rs 1,000 and Rs 500 banknotes which proved to be one of the most historic decisions of the central government. The Supreme Court on Monday upheld the decision of the government on demonetization.

Source- The Print

As per a Reserve Bank data, currency with the public has jumped to a new high of Rs 30.88 lakh crore on October 21, indicating that cash usage is still substantial even six years after the demonetisation move. At Rs 30.88 lakh crore, the currency with the public is 71.84 per cent higher than the level for the fortnight ended November 4, 2016.

The note ban move was constructed on a simple conventional logic that most people who had black money would not come forward to deposit it as they may get identified by the Society and the tax man. But those who have black money in India have been too long in the business of converting it to white clean cash. It’s a well rehearsed ritual and there exists a large matrix which assists it.

Poor people, unemployed youth, daily-wage labourers in villages and towns became “cash caddies” or “cash mules” for those who had unaccounted cash and were ready to pay small cuts. People’s Jan Dhan accounts became the parking ground for illegal money.

The high denomination 2000 note introduced didn’t gain much attraction among the poor and in rural India. It was simply too large to be used in day-to-day transactions in a country where the daily income of a household could be as low as Rs 300 a day.

According to Jayati Ghosh, Professor of Economics at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, USA said none of these objectives has been achieved. ”It is not surprising because the logic behind the move (cash is the cause of black money), the design of the move and the implementation were all completely flawed,” she said according to a report of The Financial Express.

Between demonetization and the near complete return of old currency to the banking system, there was a gap of about nine months, during which the economy faced a shortage of currency, and the petty production sector that primarily uses cash transactions, was the worst victim of it. According to reports, the cash-GDP ratio that had gone down temporarily after demonetization from its original level of 12%, climbed back again and is currently 14%.

A five-judge bench of the country’s top court passed the verdict by a majority on a batch of petitions questioning the move. One out of the five judges wrote a dissenting opinion. The petitioners included lawyers, a political party, co-operative banks and individuals.