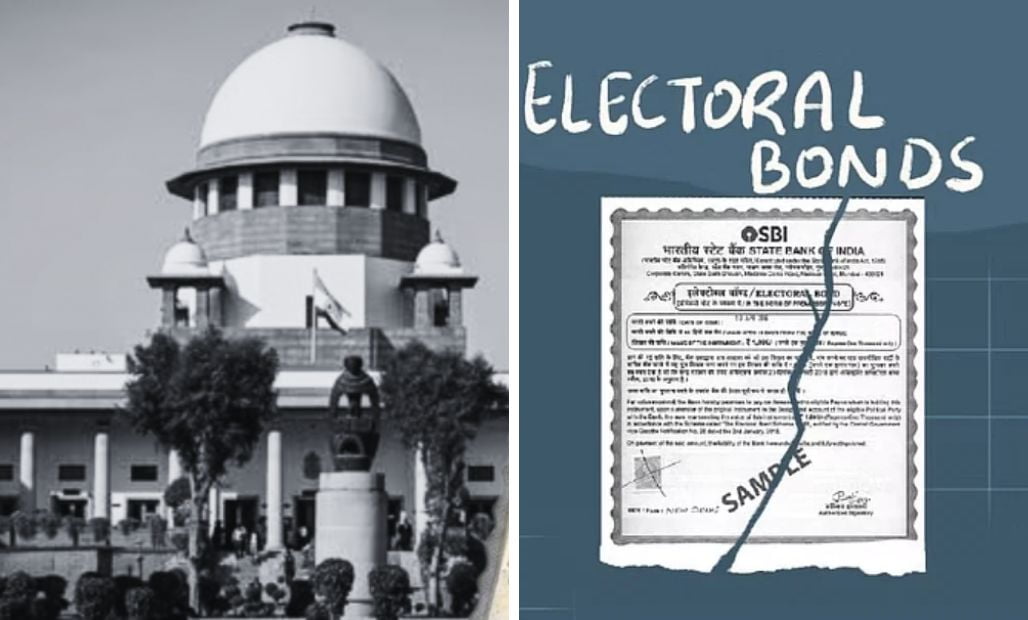

The Supreme Court recently struck down the electoral bonds scheme, just ahead of the 2024 Lok Sabha elections. This scheme, introduced by the Narendra Modi government in 2018, aimed to bring out transparency in political funding. However, a five-judge Constitution bench, led by Chief Justice DY Chandrachud, delivered a unanimous verdict, declaring the electoral bonds scheme unconstitutional.

Source: NDTV

Full Story:

Constitutional Violations:

The Supreme Court, in a dual and unanimous judgment, pronounced that the electoral bonds scheme violates the fundamental right to freedom of speech and expression under Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution. Chief Justice Chandrachud emphasized that curbing black money should not come at the expense of compromising citizens’ right to information. The court asserted that the right to privacy (Article 21) extends to political privacy and affiliation, emphasizing the need to protect this aspect of citizens’ fundamental rights.

Invalidation of Amendments:

Not stopping at the electoral bonds scheme, the court invalidated amendments made to various laws, including the Representation of Peoples Act and Income Tax laws. This move underscores the court’s commitment to upholding constitutional principles and ensuring the legality of all aspects related to political funding.

Disclosure Mandate:

The Supreme Court took a significant step by directing the State Bank of India (SBI) to disclose the names of contributors to the six-year-old scheme. Additionally, the court ordered the halting of electoral bond issuance and mandated the submission of details of bonds purchased since April 12, 2019, to the Election Commission of India. This push for transparency aims to shed light on the financial backers of political parties, particularly corporate contributors, deemed essential for maintaining a fair democratic process.

Source: The Probe

Corporate Contributions Scrutiny:

The court ruled that information about corporate contributors through electoral bonds must be disclosed, as these donations often involve quid pro quo arrangements. The court also declared amendments in the Companies Act, allowing unlimited political contributions by companies, as arbitrary and unconstitutional.

Background of the Electoral Bonds Scheme:

The Electoral Bonds Scheme, initiated in 2018, serves as an alternative to conventional cash donations for political parties. The primary goal, as emphasized by the Narendra Modi government, is to enhance transparency in political funding. Nevertheless, critics contend that the scheme’s confidential nature may breed corruption and create an uneven playing field among political entities.

Features of the Scheme:

The State Bank of India (SBI) issues bonds in denominations of Rs 1,000, Rs 10,000, Rs 1 lakh, Rs 10 lakh, and Rs 1 crore. These bonds are payable to the bearer on demand, interest-free, and can be purchased by Indian citizens or entities established in India. They may be bought individually or jointly with others and remain valid for 15 calendar days from the date of issue.

Source: Supreme Court Observer

Eligibility for Political Parties:

Political parties eligible to receive electoral bonds are those registered under Section 29A of the Representation of the People Act, 1951, having secured not less than 1% of the votes polled in the last general election to the House of the People or the Legislative Assembly.

Transparency and Accountability:

To ensure transparency, parties must disclose their bank account details with the Election Commission of India (ECI). Donations are facilitated through banking channels, and political parties are mandated to provide explanations regarding the utilization of the funds received.

Source: Republic World

Scheme and Controversies

Critics of the electoral bonds scheme argue that it contradicts its core objective of promoting transparency in election funding. The anonymity provided by the bonds is seen as benefiting the broader public and opposition parties, while the government, through the State Bank of India (SBI), could potentially identify and influence funding sources. This opens avenues for potential extortion or victimization of companies, creating an unfair advantage for the ruling party.

Amendments to the Finance Act in 2017 exempted political parties from disclosing donations received through electoral bonds, denying voters crucial information about contributors.

Source: The Hindu

The scheme’s acceptance of unlimited corporate donations, including anonymous financing from Indian and foreign companies with 100% tax exemptions, raises concerns about its impact on Indian democracy. The Supreme Court, emphasizing the right to know in the electoral context, faced challenges against the amendments, claiming unconstitutionality and violation of fundamental rights.

Electoral bonds, offering anonymity to donors but not to the government, pose a threat to free and fair elections. The government’s access to donor details through the SBI enables potential manipulation of information to influence election outcomes. The removal of pre-existing limits on political donations under the scheme further fuels concerns about crony capitalism, allowing well-resourced corporations to shape electoral outcomes.