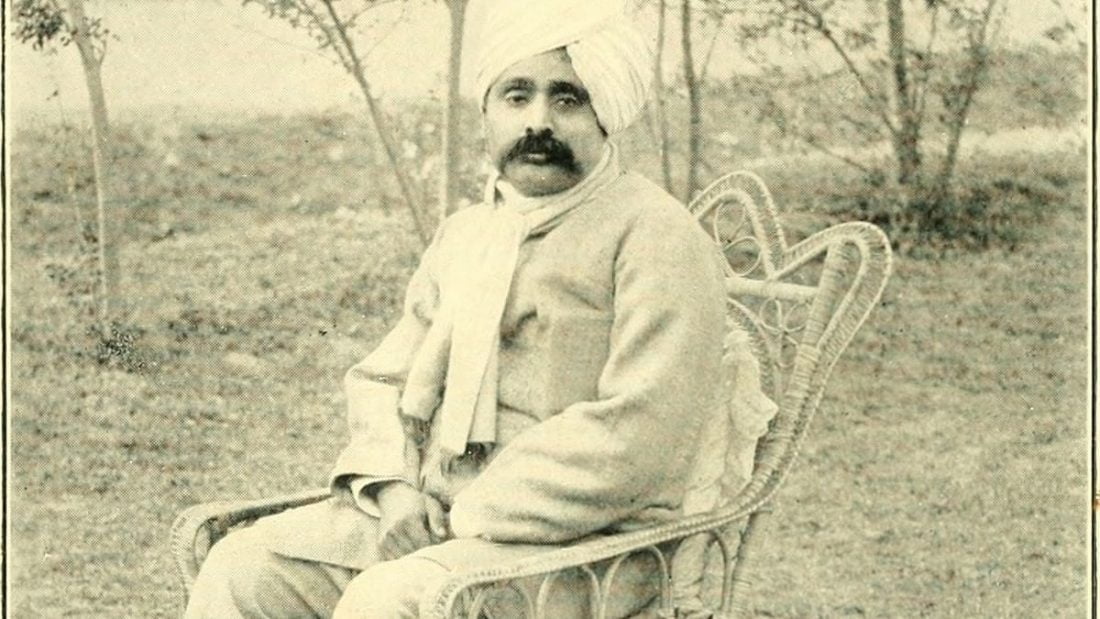

The last few years in India, fuelled by divisive politics and communalism, have seen Hindutva activists claim Lala Lajpat Rai to be one of their own, sharing their ideology and agenda. There’s no doubt that Rai was a champion of assertive Hindu politics, exemplified by his participation in both the Punjab Hindu Sabha in 1909 and the Hindu Mahasabha in the mid-1920s.

However, he saw Hindu politics very differently from the Hindu nationalism that sought to forcefully integrate India’s religious minorities into Hindu culture or banish them from the nation.

In 1915, he declared that “religious nationalism” arose from a “narrow sectarianism” that could not be “truly national” since “religion is a matter of individual faith” that “must not interfere with the civil life of the country”.

In 1918, he published “The Problem of National Education”, a book in which he argued that “we modern Indians can be as well proud of a Hali, an Iqbal, a Mohani as of Tagore, Roy and Harishchandra. We are proud of Sir Syed Ahmed Khan as of Ram Mohan Roy and Dayanand”, adding that “the educated Mussulman does not withhold his admiration from the religious, philosophic, and epic literature of India, just as the educated Hindu reckons the Taj and Fatehpur Sikri among the glories, not of Muslim but of Indian architecture”.

Moreover, he argued that Indians must develop a pluralist national culture for themselves, saying that “national festivals are the milestones on the road to national life. Hindus and Muslims would do well to take part in each other’s festivals and religious occasions like Basant Panchami, Baisakhi, Dussehra, Diwali, Muharram and Shab-e-Barat .

A comprehensive view of his ideology can be summed up through his quote “To require India to coalesce into a nation with one religion and one tongue… would revive the medieval idea of one empire, one people, one church.”